GREEK MYTHOLOGY AND FABLE FOR THE YOUNG.

Tell me a story.

"Tell me a story". This is what most children say as soon as they can speak and understand. In every country and every civilization. And now it is happening to you.

You are visiting your girlfriend who has a 5-year old brother Johnny with the annoying habit of hanging around too long. You wish he would go to bed. So he finally does, and when you are just about to leave when he says:

"Tell me a story before I go to sleep".

"OK", you say to yourself, "Let's get it over with, it should be relatively easy".

So you start, "One day, as I was watching baseball, the doorbell rang."

Johnny could barely stifle a yawn. You try again and again and it is not working. "This kid will never go to sleep", you say to yourself.

"So what do you want to hear about?" you ask.

"Tell me about old old times, about monsters, bad men, gods, and heroes, beautiful princesses and dragons".

"Well, OK, this might just work", you think. "It shouldn't be too hard".

Let's create a Hero.

So you finally decide to tell Johnny a story about a hero. So you start:

"There is a hero. He is called Bill. He lives in the next house".

Johnny interrupts: "There is no hero called Bill. And I know the person in the next house. He is no hero".

"Here we go again!" you think, "this kid will never let up, he wants a specific story".

So you sigh and start again: "There was once a hero. He was named Edward. He lived in Pittsburgh"

"Oh, OK. What did Edward do".

"Well, his boss wanted him to work late but he refused".

"That is no hero. And the story is boring. Tell me about a real hero".

At this point you realize you are in some serious trouble. This requires some real thinking.

"Tell you what, kid. Let me think a little. Let me go into the library, and I will come back in an hour and tell you a story you will really like".

So you do a bit of thinking and a bit of reading and come up with the following formula for a hero:

(1) The hero's mother is a royal virgin,

(2) His father is a king, and

(3) Often a near relative of his mother, but

(4) The circumstances of his conception are unusual, and

(5) He is also reputed to be the son of a god.

(6) At birth an attempt is made, usually by his father or his maternal grandfather, to kill him, but

(7) He is spirited away, and

(8) Reared by foster-parents in a far country.

(9) We are told nothing of his childhood, but

(10) On reaching manhood he returns or goes to his future kingdom.

(11) After a victory over the king and/or a giant, dragon, or wild

beast,

(12) He marries a princess, often the daughter of his predecessor, and

(13) Becomes king.

(14) For a time he reigns uneventfully, and

(15) Prescribes laws, but

(16) Later he loses favor with the gods and/or his subjects, and

(17) Is driven from the throne and city, after which

(18) He meets with a mysterious death,

(19) Often at the top of a hill.

(20) His children, if any, do not succeed him.

(21) His body is not buried, but nevertheless

(22) He has one or more holy sepulchres.

Now you are in business! You start again.

"There once was a hero. His name was Zebedion. He lived many years ago. His father was a king, but his real father was a god. The king hated him. He decided to kill Zebedion. But his mother saved him. He grew up, slew the bad dragon, killed the king, and married the king's daughter.

Do you want to hear about this story? If you do, I will tell it"

Johnny is in heaven. And soon you can re-join your girlfriend.

The Greeks excelled in these kinds of myths and stories.

So why read them?

Can one be called educated if he/she is not knowledgeable of the Hellenic mythology? Hardly. This is what the great English poet, Shelley, said: "We are all Greeks. Our laws, our literature, our religion, our arts, have their root in Greece." In my youth I have found mythology and fables interesting. They were part of my background and shaped my life. Why?

At this point I have a decision to make. I can outline several reasons, intellectual, psychological, artistic, and try to influence you. But that's not how I came to love mythology. That love came from the delight I got from reading the detailed stories. Not outlines, not abbreviations, but the most complete versions. They say, "the devil is in the details". I don't know about the devil, but I know that the beauty of the stories is in the details; the creative, scintillating inventiveness of the Greeks is stunning. By no means do I encourage sexual promiscuity, but I can't help but smile at that old lecher, Zeus. He pursues maidens in myriad guises: as a shower of gold, as a swan, as a bull, and many more. His wife, Hera, is equally imaginative in posing obstacle after obstacle to her amorous husband. Similarly, the legendary Hercules is not only strong, any dumb hero can be that! But he also has to learn to perform service, a much higher degree of difficulty. And not any service, but 12 of the most imaginative ones, each teaching a lesson. In the body of this paper I will discuss the myths about Zeus and Hercules in some detail and point out the highlights.

So why else should you read them?

Because they are wise. The stories are eternal. They stories survived because they are the best Mankind has to offer, and because they deal with situations that are timeless. They matter today as much as at any time. That is the hallmark of great literature. They arose from our collective unconscious and continue to speak to us because of our psychological need for understanding and resolution.

Because their psychological insights are unparalleled in the history of Mankind. From the Oedipus complex to fear of castration, from penis envy to blood feuds, from conflict between duty and love, from the dangers of excessive self-love, to the hubris of trying to fly too high, they have it all. Nothing has been done in the last 2200 years that equals these insights, the nurturing effect of the stories.

Because they have infused Literature, Music, Painting, Sculpture, with eternal sources of inspiration. Except the Bible, nothing equals their creative influence.

As I said, it is lucky person who has such heritage. Maybe it's time to dip into it and see what they are all about. And see if our latest baseball hero is not an incarnation of Hercules, if Madonna is not our modern Helen of Troy.

In the following I would like elaborate some of these points.

Three myths.

Zeus (Jupiter for the Romans).

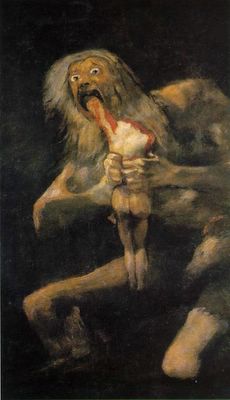

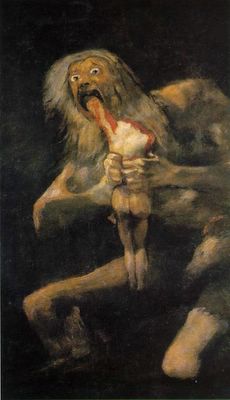

What can you expect of a god whose father swallowed all his siblings and is about to swallow him? But that is what happened to Zeus (known as Jupiter to the Romans. In one of the typical prophecies the Greeks loved, his father the king, Cronos (known as Saturn to the Romans), was told that one of his children would depose him. I have never understood why people react this way? If they believe that the prophecy is true then surely they can't do anything to circumventing it. If they think they can outsmart the prophecy, it means they really don't believe it. Well, needless to say, Cronos believed the prophecy, and having already swallowed five of his children was ready to do likewise with Zeus. Cronos's wife, Rhea, outsmarted her husband, gave him a stone wrapped in clothes to swallow. Cronos swallowed the switch. Zeus survived. Cronos (Saturn) swallowing one of his children is one of the greatest paintings of the Spanish artist, Goya. It is also one of the most frightening in the history of painting. It illustrates the primordial terror Geek myths can evoke. The Greeks never shrank from the darkest night of the soul.

So Zeus, of course, survived. When Zeus had grown up, he had Cronos's attendant, Metis, give Cronos a drug, which forced him to disgorge first the stone and then the children whom he had swallowed. And with the aid of his brothers and sisters Zeus waged war against Cronos and the Titans. This is how Zeus became the ruler of Heaven.

Much as I would like, I cannot due justice of the wealth of myths that are associated with Zeus. Each story begets another story. Instead I would like to concentrate on two aspects of the stories, the punishments he meted out, and his romances. Zeus was no shrinking violet when it came to dealing with his adversaries. The slightest disrespect met with swift, imaginative, punishment. For instance, Sisyphus was sentenced to the Underworld to push a boulder up a slope. Whenever he almost succeeded, the boulder plunged and he had to start again. Forever. Sisyphusian labor, one that never gets done, has become a byword in Western literature. An almost as imaginative punishment befell Tantalus. He was sentenced to hang from the bow of a tree, almost able to quench his thirst from a pond below. Whenever he was about to reach it, the water receded. Similarly, whenever he reached for fruit on the tree, it too shrank from his reaches. Tantalusian torture too has come to live in Western art. And of course, there was Prometheus, who according one myth helped mankind by giving him life-sustaining fire. For this, Zeus tied him to a rock and had a vulture constantly tearing his liver. Fire-giving Prometheus became a symbol of Western art. Countless plays, paintings, and poems celebrate the story. It illustrates the perils of giving knowledge (for that is what the fire symbolizes) to man. And also knowledge itself. For me, the story parallels that of Adam and Eve, who were banished from Paradise for eating from the tree of knowledge. The Greeks too knew the danger of knowledge and the independence from god it encourages. It's time to move on to lighter topics, or at least to more amorous ones. Zeus seemed to have been lucky in both wars and love. The maidens he pursued are a legion. His imagination and persistence is amazing. Not for him the brute force, but the art of transformation and disguise.

But before I do that, I should mention how history repeats itself. Zeus coveted the maiden Metis, who assumed many shapes in vain to avoid Zeus. She became his first wife. It had been foretold that she would bear a son who would be the lord of heaven. As they say, the apple doesn't fall far from the tree, from fear of that prophecy, Zeus swallowed her while pregnant. When the time came for the birth to take place inside Zeus, Prometheus, or Hephaestus smote the head of Zeus with an axe, and, Zeus's child, Athena, fully armed, leapt up from the top of his head at the river Triton.

But I have to digress again. It is the beauty of the Greek myths that they can be read at many different levels. It would be overly simplistic to read the many myths about Zeus and women as simple womanizing. I don't think the Greeks looked at it that way. On one level, each generation needs to feel that it has divine origin. Almost all of Zeus's offsprings became important heroes from whom entire nations sprung. Hence these stories were important to the descendents. The stories also contain much encoded wisdom, as exemplified by the story of Semele, one of the maidens loved by Zeus in disguise. At the height of love, Zeus promised Semele to fulfil any wish she would care to make. Foolish promise! Semele has longed to see Zeus in his real form, something no mortal could endure. The horrified Zeus tried to talk her out of this suicidal request; in vain. So he appeared in his blinding splendor, and Semele was burnt by the fire. Clearly, the story talks about man's desire to behold god, and the danger of beholding the terrible aspect of god. This is far more than a simple story of conquest! And in a way it is touching to see the loving Zeus, protecting his beloved, and trying to make sure that no harm befalls the offsprings; not always an easy task.

I cannot do justice to all of Zeus's conquests, but here is a list, not necessarily alphabetically.

Aegina, daughter of the river god Asopus, was carried off by Zeus, who had taken the shape of an eagle, to the island then named Oenone but now called Aegina after her.

Antiope too was loved by Zeus. Zeus, who seldom repeated his tricks twice, took the shape of a Satyr to approach her. Zeus, apparently in his normal form, also made love to Leto. For this, Zeus's jealous wife Hera hunted her over the whole two continents Finally in Delos, she gave births to two gods, Apollo and Artemis. Zeus seduced Callisto taking the shape of Artemis. To make sure she would not be detected by Hera, Zeus transformed her into a bear. Hera detected the ruse and had Artemis to shoot the wild beast. Zeus approached Eurymedusa, daughter of Cletor, after having assumed the form of an ant.

At least on one occasion Zeus has shown prudent restraint. Even though he loved the Nereid Thetis, upon hearing the prophecy that her son would be mightier than his father he withdrew. Zeus then, bade his grandson Pelus to marry her. From this union the hero Achilles was born. I am sure you know his pivotal role in the Trojan War. Niobe was the first mortal woman with whom Zeus consorted. She is a daughter of Phoroneus, who is said to be the first man.

The indefatigable Zeus seduced Io while she was a priestess of Hera. When detected by his wife, Hera, Zeus turned Io into a white cow by a touch and swore that he had not known her.

Zeus fell in love with a Phoenician princess called Europa, and having taken the form of a bull, he carried her off and took her across the sea to the island of Crete. This is the origin of the name of the continent, Europe.

The above should give you small idea of Zeus's amorous activities. I have reserved two more in another section later in this article.

It is now time to move to the greatest of Greek heroes, Heracles (or Hercules). The link, of course, is another of Zeus's romance, as describe below.

Alcmena was the last mortal woman with whom Zeus lay. Zeus took the form of Amphitron (her husband) to deceive her. When Heracles, Zeus's child by her, was about to be born, Zeus declared among the gods that the next descendant of Perseus, who would be born next would reign over Mycenae. He fully expected Heracles to be the person. But he, once more, failed to reckon with the jealous Hera who conspired to retard Alcmena's' delivery, and contrived that her favorite, Eurystheus should be born prematurely. By this ruse, Eurystheus became king of Mycenae, and Heracles his subject.

Heracles (Hercules for the Romans).

The most famous of the Greek mythological heroes, Heracles is known to most people for his legendary strength, and for his labors (The Labors of Hercules).

As I indicated above, the story of Hercules was embroiled in treachery between Zeus and Hera.

When Heracles was eight months old, Hera, desiring his death, sent two serpents to his bed. But he strangled the beasts with his hands. And when he was eighteen years old he slew the Lion of Cithaeron. In a story too complicated to tell, Heracles was driven mad by Hera, and killed his wife. As punishment he was compelled to serve Eurystheus for 10 years, during which Eurystheus made him perform 12 of the most seemingly impossible tasks (the labors).

A later myth indicates the choices many heroes, as well of most of us, had to make. When Heracles was about to enter adult life he met two women describing each a different road through life. One called herself Happiness (Eudaimonia), but said her critics call her Vice (Kakia) and described an easy road, while the other, called Virtue (Arètè), described a road of hardship and hard labor. As you will see, Heracles chose the latter, indicating a submission to god's will rather than emphasizing his brute strength. His first labor was to destroy the Numean Lion. Heracles shot an arrow at him, but when he perceived that the Lion was invulnerable, he broke its neck with his bare hands. As a second labor he was ordered by Eurystheus to kill the Lernaean Hydra, offspring of Typhon and Echidna, a monster with nine heads, one of them being immortal. He chopped all heads and the immortal one he buried putting a heavy rock on it. As a third labor he was ordered to bring the Cerynitian Hind alive to Mycenae. The Hind had golden horns and was sacred to Artemis. So Heracles did not wish to wound it, but at the end he shot it just as it was about to cross a river. He caught it and hastened through Arcadia towards Mycenae. But Artemis and Apollo met him, and rebuked him for attempting to kill her sacred Hind. But Heracles put the blame on Eurystheus, pleaded necessity, and so he appeased Artemis's anger and carried the Hind alive to Mycebae. As a fourth labor he was ordered to bring the Erymanthian Boar, which ravaged Psophis, alive. The fifth labor was to carry out the dung of the cattle of Augeas, king of Elis, in a single day. Heracles went to Augeas, and without revealing the command of Eurystheus, said that he would carry out the dung in one day, if Augeas would give him the tenth part of the cattle. Augeas was incredulous, but promised. Having taken Augeas' son Phyleus to witness, Heracles made a breach in the foundations of the cattle-yard, and then diverting the courses of two rivers, he turned them into the yard. When Augeas learned that this had been accomplished at the command of, he would not pay the reward. When arbitrators were called Phyleus bore witness against his father and Augeas ordered both Phyleus and Heracles to leave Elis.

I am not going to describe all the labors; that would be a Herculean task. But I will mention that the ninth labor was to fetch the Belt of Hippolyte, queen of the Amazons. She had the belt of Ares for being the best among the Amazons. Heracles was sent to fetch it because Admete, daughter of Eurystheus, desired to get it. Heracles killed Hippolyte and stripped her of her belt.

You will have to read the rest of the labors, and find out what happened to Heracles--some story. But before I leave this section, I want to indicate another reason why I like the Greek myths. This can be illustrated with the following events involving Heracles. In one of his journeys he came to Libya, where there was a ruler, named Antaeus, who used to kill strangers by forcing them to wrestle. Antaeus was son of Gaia, the goddess of the Earth. He became stronger when he touched the Earth because he derived his strength from it. At first Heracles was unable to defeat him because he kept regaining his strength. Finally, Heracles killed him while holding him in the air. Antaeus is not a nice character, but the story at another level illustrates that we are invincible while in touch with our mother, or home, our home base, our background. Another lovely reason to revisit the Greek myths.

Theseus.

One of the most important heroes, especially important for Athens. He was the son of either King Aegeus (from which the Aegean Sea gained its name, sea below) or Poseidon. Before King Aegeus left home, he placed his sword and sandals beneath a huge rock and told his wife Aethra that when their son, Theseus, could lift the rock he was to bring the gifts to his kingdom in Athens. At the age of 16 Theseus lifted the rock and began his journey, during which he freed the countryside of various monsters and villains. When Theseus arrived at Athens, Medea, then wife of Aegeus, tried to kill him. Aegeus, however, recognized the sword and sandals, saved Theseus, and exiled Medea. Theseus subsequently had numerous adventures. His most famous exploit was against the Minotaur of King Minos of Crete. Athenians, who had been at war with King Minos of Crete, were forced by him to send every year seven youths and seven young women as a tribute to the Minotaur (half bull, half man). Theseus insisted on being one of the seven youths and seven maidens of Athens to be sacrificed to the monster as an annual tribute. He promised his father that if he were successful in killing the Minotaur he would on his return voyage replace his ship's black sails with white ones. Ariadne, daughter of King Minos, fell in love with Theseus and gave him a magic ball of thread to be dropped at the entrance of the labyrinth; it led Theseus to the Minotaur, which he killed, and he then followed the unwound thread back to the entrance. He left Crete with Ariadne but abandoned her at Naxos. The myth is clearly an allegory, symbolizing Athens' anger over having to pay the heavy taxes to Minos, its resolution brought about the myth of killing the Cretan man-bull.

When Theseus reached home he forgot to raise white sails. Aegeus saw black sails, and, thinking his son dead, the grief-stricken father threw himself into the sea, thereafter called the Aegean. As king of Athens, Theseus instituted several reforms, most notably the federalization of the scattered Attic communities. Theseus abolished all local courts and administrative offices, and made Athens the sole location of government. Then, as he had promised, he surrendered his royal power. He journeyed to the land of the Amazons, where he abducted Antiope, who bore him Hippolytus. A vengeful Amazon army invaded Athens, but Theseus defeated it. Some say Antiope died fighting beside him in the battle; others claim that Theseus killed her when she objected to his marriage to Phaedra. Later Theseus was imprisoned in Hades until Hercules rescued him. Upon his return to Athens, he found his once great kingdom a turmoil of corruption and rebellion. He regretfully sailed away and came to rest at Skyros, where he was treacherously murdered by King Lycomedes. Although Theseus is generally thought of as legendary, the Athenians believed he had been one of their early kings.

Why do Myths work?

So you may begin to wonder: why do hero myths work? Or more broadly, why do myths work? It is clear that for a myth to be universally meaningful, to survive over generations and even centuries, they have to be in a particular way. Not every hero story works, and not every other supernatural story becomes a myth.

It appears that we are constructed in such a way that our psyche, or our soul, is pre-tuned to receive certain stories. Only those that fit our soul's template become lasting. The great Swiss psychologist, Carl Jung, believed that myths arise out of our collective unconscious, a repository of Mankind's psychological history. If he is correct, it makes sense that only these ones will find resonance in us. And the equally great Austrian psychologist, Sigmund Freud believed that only those myths survive that contain something deeply psychologically meaningful.

The Greek myths, and especially the hero myths, in which the Greek excelled, satisfy these criteria. I think they encode two separate but parallel experiences. The same way as an embryo in its development recapitulates the evolutionary development of the entire species; the hero myths speak of individual as well as general human experiences. For the individuals, for us, the hero myths speak to our subconscious desire to slay, to supplant our father and re-occupy our mother's undivided affection and even her bed. They describe our secret belief that we are somehow special, surely God's favorite, surely of higher birth than our own. The myths describe our coming of age after hard struggle.

There is a near parallel for the development of Mankind in the era of rationalism that the Greeks ushered in after many centuries of darkness and superstition. The heroes fulfil an important role, they stamp out tyranny, and in their quest they kill monsters which stand for fear, chaos, and unreason. Unfortunately, in a male society these monsters were often female, the feminine for the Greeks, as indeed for most men, represents that which is irrational and to be feared. Thus the Greek gods have supplanted the previous Great Mothers and Goddesses, reflecting the change from matriarchal to patriarchal society. The myths reflect this change.

We are still mostly the descendents of the male Geek society, the recipient of their male-inspired and male-oriented myths. That is why they continue to exercise fascination in most of us, especially in artist. There are other types of myths, which were alien to the Greeks. There are other types of myths, which were alien to the Greeks. They did not do heroines well if at all; admittedly they had goddesses, but they were either sex symbols (Aphrodite/Venus), chaste hunters (Artemis), or wise/warlike (Athene). They had monsters but did not do truly evil well. They had, interestingly, nothing equivalent to Darth Veder or the Shadow in Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, for instance. For these we have to turn elsewhere, as well as for truly female-oriented myths. But for the rest, the Greek myths survive and keep inspiring our subconscious and our art, which so often renders the subconscious visible.

There is another type of story that also has its origin with Ancient Greece, the fable. It shares some characteristics with myths. I will also touch on it later in this article.

The Influence of Greek Mythology on Western Art, Literature and Music.

Artists were some of the first who recognized the timeless importance of Greek mythology for Western life. In fact, Greek mythology, along with the Bible, was the most important creative fertilizer of arts. I would just like to indicate this by a few examples. Along the way I will also sketch two of the stories that inspired art. It will give you an idea of the richness of the Greek myths. I have borrowed the description of myths from my favorite website: http://www.hsa.brown.edu/~maicar/. You can visit it for more information.

The influence of Greek mythology on music was mostly in opera. From the 17th century until the beginning of the 20th century it dominated the operatic topics. Because I have written a separate article on this, I do not want to repeat myself. Those interested can look at it in my web site: http://home.att.net/~paul.hoffman1/grdrmpsound.htm

Here I would like to mention the three highlights, Richard Strauss's Elektra and Ariadne auf Naxos and Enesco's Oedipe. If you like music, or even if you don't, I urge you to try some of these, especially in a video format.

The next important field would be literature. Here, however, there is a paradox. The myths are an important literary source, but the three great ancient playwrights, Aeschylos, Sophocles, and Euripides have dealt with these topics so superbly that few subsequent writers dared to follow them.

It would be more profitable to indicate the influence of mythology on painting and sculpture, by using two myths and their interpretations in the arts. The myths themselves are interesting, demonstrating the best features of Greek mythology, and they have inspired many works of art. I have chosen two of my favorites, surely pinnacles of Western art. The two myths will be about, Perseus, and Leda and the Swan.

Perseus

Danae's father King Acrisius ofArgos once questioned the oracle about the future. The oracle prophesied that Danae would give birth to a son who would kill him. Fearing that, the king built a brazen chamber under ground and there he guarded Danae. Zeus, who lusted after Danae had intercourse with her in the shape of a stream of gold, which poured through the roof into Danae's lap. From that imaginative union Perseus was born. When her father afterwards learned that she bore a child, he would not believe that she had been seduced by Zeus. He cast her with her child in a chest, and cast it into the sea. The chest was washed ashore on the island of Seriphus, which is one of the islands called Cyclades, where Polydectes was king.

Polydectes, who colonized Seriphus and there became king, fell in love with Danae but was unable to be with her because of Perseus's. And as a time-honored method to get rid of uncomfortable persons he gave Perseus a dangerous assignment far away. Polydectes sent young Perseus to fetch and bring back the head of the Gorgon, Medusa, a seemingly impossible task, since anyone who looked at Medusa died. Fortunately, Perseus had help; he was guided by Hermes and Athena. In order to find his way he met the Graeae, who were sisters of the Gorgons, old women from birth. The three Graeae had but one eye and one tooth between them, and these they passed to each other in turn. Perseus, taking their tooth and eye, compelled them to show him the way to the Nymphs who had the winged sandals and a wallet (kibisis). Once the Graeae had shown him the way, he gave them back the tooth and the eye, and coming to the Nymphs, he managed to get the sandals and the wallet.

He then slung the wallet about him, fitted the sandals to his ankles, and put the Helmet of Hades on his head, which made him invisible. And having received from Hermes an adamantine sickle he flew to the ocean and caught the Gorgons asleep. With Athena guiding his hand, and looking on his brazen shield, in which he could see reflected the image of Medusa without injury to himself, he beheaded her and put the head in the wallet.

This story has been a source of a number of great art works, none greater than Benvenuto Cellini's Perseus. It is one of the greatest Renaissance sculptures, resembling and rivaling Michelangelo's famous David. It shows a superbly muscled Perseus triumphantly emerging with the severed head of Medusa. Seldom has a work of sculpture capture the moment so perfectly as this. The work, a perfect blend of Italian classicism and Greek dramatic gestures, deserves to be better known.

Cellini's Perseus

Leda and the Swan.

Zeus consorted with the beautiful Leda in the form of a swan. Apparently Leda was no shrinking violet, since on the same night she also lay with Tyndareus. Four children were born of the two unions. Polydeuces and Helen, children of Zeus, were born from an egg laid by Leda, while Castor and Clytaemnestra were children of Tyndareus.

This story contains in it the beginning of the great Greek epic story about the Trojan War. Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world, of course, was the cause of the war, while Klytemnestra (in English spelling) was the wife of one of the Greek heroes, Agamemnon, whom she had killed. In return, she was killed by their son, Orestes. The Trojan War provided the source material for the Iliad, while the story of Agamemnon and Kytemnestra, was re-told many times, maybe most dramatically in Aeschylos's Oresteia.

The story of Leda and the swan became the creative source of many subsequent paintings, and at least one great, oft-anthologized poem by the Irish William Butler Yates, given below the painting.

My favorite painting is that by Leonardo da Vinci, left to us only in a copy. It depicts a surprisingly loving Zeus in the form of a swan, affectionately nuzzling Leda, while the four children, are about to be hatched form the two eggs. If Helen became half as beautiful as her mother, Leda is on this picture, I can see how she could launch a thousand ships in the Trojan War. The painting has all of Leonardo's hallmarks, including for me the famous Mona Lisa-like half smile, as if she could already foresee the mayhem in Troy and the tragedy of the house of Atreus (Agamemnon, Klytemnestra, Electra, Orestes, etc.) that followed from her union with Zeus.

Copy of Da Vinci's Leda and the Swan

Leda and the Swan

A sudden blow: the great wings beating still

Above the staggering girl, her thighs caressed

By the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill,

He holds her helpless breast upon his breast.

How can those terrified vague fingers push

The feathered glory from her loosening thighs?

And how can body, laid in that white rush,

But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?

A shudder in the loins engenders there

The broken wall, the burning roof and tower

And Agamemnon dead.

Being so caught up,

So mastered by the brute blood of the air,

Did she put on his knowledge with his power

Before the indifferent beak could let her drop?

by William Butler Yeats

The Fable.

Nearly as old as the Olympics, bigger than Dinosaur, older than the Titanic, more complex than Pokemon and more of them than Beanie Babies are Aesop's Fables. Every day hundreds of entire classrooms of kids from all over the world read them, learn from them and enhance their living experience by it. So let us see what are these Fables?

In addition to the myths, the Greeks also excelled in a special kind of story the fable. You may have read several of them in your childhood. The distinction between mythological stories, tales and other forms is not easy, as you can see from the following:

The Tale, the Parable, and the Fable are all common and popular modes of conveying instruction. The Tale consists simply in the narration of a story either founded on facts, or created solely by the imagination, and not necessarily associated with the teaching of any moral lesson. The Parable is the designed use of language purposely intended to convey a hidden and secret meaning other than that contained in the words themselves; and which may or may not bear a special reference to the hearer, or reader. The Fable partly agrees with, and partly differs from both of these. The Fable aims at one great end and purpose--the representation of human motive, and the improvement of human conduct. It cleverly conceals its design under the disguise of fictitious characters, by clothing with speech the animals of the field, the birds of the air, the trees of the wood, or the beasts of the forest, that the reader shall receive advice without perceiving the presence of the adviser. The moral of the story is easier to accept this way.

The imagination of Aesop, who single-handedly invented the Fable, is vast. Of his many Fables I have picked three which illustrates them well. You may want to see whether you can figure out the moral of the stories. In case you are too lazy to do so, below each story I am also giving the morals.

THE MAN AND HIS PURCHASER.

A man wished to purchase an Ass, and agreed with its owner that he should try out the animal before he bought him. He took the Ass home and put him in the straw-yard with his other Asses, upon which the new animal left all the others and at once joined the one that was most idle and the greatest eater of them all. Seeing this, the man put a halter on him and led him back to his owner. On being asked how, in so short a time, he could have made a trial of him, he answered, 'I do not need a trial; I know that he will be just the same as the one he chose for his companion.' MoralA man is known by the company he keeps. A perfect example of why parents are concerned about your friends.

THE ANT AND THE GRASSHOPPER.

In a field one summer's day a Grasshopper was hopping about, chirping and singing to its heart's content. An Ant passed by, bearing along with great toil an ear of corn he was taking to the nest. "Why not come and chat with me," said the Grasshopper, "instead of toiling and moiling in that way?" "I am helping to lay up food for the winter," said the Ant, "and recommend you to do the same." "Why bother about winter?" said the Grasshopper; we have got plenty of food at present." But the Ant went on its way and continued its toil. When the winter came the Grasshopper had no food and found itself dying of hunger, while it saw the ants distributing every day corn and grain from the stores they had collected in the summer. Then the Grasshopper knew:

Moral

It is best to prepare for the days of necessity

THE HARE AND THE TORTOISE.

A Hare one day ridiculed the short feet and slow pace of the Tortoise. The latter, laughing said: "Though you be swift as the wind, I will beat you in a race." The Hare, deeming her assertion to be simply impossible, assented to the proposal; and they agreed that the Fox should choose the course, and fix the goal. On the day appointed for the race they started together. The Tortoise never for a moment stopped, but went on with a slow but steady pace straight to the end of the course. The Hare, trusting to his native swiftness, cared little about the race, and lying down by the wayside, fell fast asleep. At last waking up, and moving as fast as he could, he saw the Tortoise had reached the goal, and was comfortably dozing after her fatigue. MoralSlow but steady wins the race.

So why should you read Greek Fables and Mythology?

Because the stories belong to all Mankind. Even more, they belong to Western civilization, which became its heir. And finally, because as descendents of the Greeks you are inheritors of these priceless myths. And civilizations lose they vitality and ultimately perish if they do not retain what is best of their past. Greek mythology is one of these.

SUMMARY:

This article discussed why Greek Mythology and Fable are still relevant for the young. It described several of the most important myths, pointing out their most interesting features. It discussed why myths work, and how they have influenced Western Literature and the Arts. It indicated the following main reasons for reading them:

1. They are plain fun. They contain exciting stories, interesting characters, gods, goddesses, heroes, bulls, maidens, at least as interesting as those of modern stories.

2. They are wise. The stories are eternal. They stories survived because they are the best Mankind has to offer, and because they deal with situations that are timeless. They matter today as much as at any time. That is the hallmark of great literature. They arose from our collective unconscious and continue to speak to us because of our psychological need for understanding and resolution.

3. Their psychological insights are unparalleled in the history of Mankind. From the Oedipus complex to Narcissism, from penis envy to blood feuds, from conflict between duty and love, they have it all. Nothing has been done in the last 2200 years that equals these.

4. They have infused Literature, Music, Painting, Sculpture, with eternal sources of inspiration. Except the Bible, nothing equals their creative influence.

5. Because the stories belong to all Mankind. Even more, they belong to Western civilization, which became its heir. And finally, because as descendents of the Greeks you are inheritors of these priceless myths. And civilizations lose they vitality and ultimately perish if they do not retain what is best of their past. Greek mythology is one of these.